Magazine covers can help identify sentiment extremes that accompany major market tops and bottoms

5/2/2016 12:25 PM

The following is an updated column that originally appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of SENTIMENT magazine, and was reprinted in the market commentary from the May 2016 edition of The Option Advisor, published on April 21. For more information or to subscribe to The Option Advisor, click here.

Imagine you have a time machine and you set it for November 1992. The U.S. economy is slowly emerging from the 1991 recession and U.S. auto sales have receded to a level that was to mark a low point for the next 16 years.

This picture of a struggling economy is reinforced when you pick up a copy of the November 9, 1992, issue of TIME magazine at an airport magazine counter and notice the cover story is titled «Can GM survive in today’s world?»

Your next stop in time is December 1993. The economic recovery has accelerated, and U.S. auto sales have recovered smartly from their depressed 1992 levels. You stop at the same airport magazine counter (which you note has not changed much at all), but there’s something very different about the December 13, 1993, cover of TIME. In fact, it displays bust-style photographs of the CEOs of each of the «Big 3» U.S. automakers lined up Mt. Rushmore-style. And the cover is captioned «The Big Three — How Detroit is shifting into high gear.»

You understand that 13 months just passed in what seemed like moments due to your marvelous machine, but you still find this contrast in covers to be a bit unsettling. «It was 13 months, not 13 years,» you say to yourself. «How could the views on the U.S. auto industry have morphed from despair to euphoria in just a shade over one year?»

You return to the present day, and while pulling up some stock price charts, you get a flash of inspiration. You decide out of a growing curiosity to check the price for GM shares in November 1992 and compare it to levels in December 1993. And then you stop in your tracks when you note that GM shares were trading at about $28 in November 1992 and by December 1993 they had soared to just above $55.

«So,» you say to yourself, «investors who got caught up in the gloom, doom, and despair of November 1992 and who proceeded to sell their GM shares would have missed a recovery of about 80% over the next 13 months.» And what of the investors who were caught up in the euphoria of the Mt. Rushmore cover in December 1993 and bought GM shares in anticipation of Detroit «shifting into high gear»? Your pulse quickens when you discover that just one year later — in December 1994 — GM shares had skidded by 33%, all the way back to $35.

«Can it be a coincidence,» you ask yourself, «that the extremes in sentiment as expressed in these two magazine covers proved to be nothing short of disastrous to anyone who tried to act based on these views by trading in GM stock? And if it was no coincidence, what is the principle of investing that governs this contrarian phenomenon?»

My quick answers to those two questions are «No, it was not a coincidence,» and «Markets bottom when investors are in despair and markets top when investors are euphoric.»

And I’ll go a step further in the rest of this article and make the case that the information you can glean from something as simple as the magazine cover can help you to identify these extremes in investor sentiment, much to the benefit of your portfolio.

The Premise of Sentiment

The central principle of contrarian investing is very basic and very difficult to dispute: When «everyone» is bullish, buying power has been exhausted. A top is at hand, and the next major move is down. When «everyone» is bearish, selling pressure has been exhausted, a bottom is at hand, and the next major move is up. The difficult part lies in correctly identifying these situations, and doing so in real time rather than after the fact. Everyone now «knows» we had a technology stock bubble that culminated in early 2000. But back then, in the moment, there were far more believers than skeptics — even among experienced investors — in the sustainability of the tech stock rally.

It is both logical and demonstrable that the key to determining the points at which either buying power or selling pressure is exhausted is to identify extremes in investor sentiment. When investor sentiment is in fact euphoric after a sustained rally, this is strong confirmation that the vast preponderance of money that can be attracted to the market has already been committed, and this exhaustion of sideline buying power will soon lead to a top. Similarly, when investors despair of the market after a sustained decline, the accompanying exhaustion of selling pressure will be followed by a market bottom.

Magazine Covers: A Tell-Tale Sign

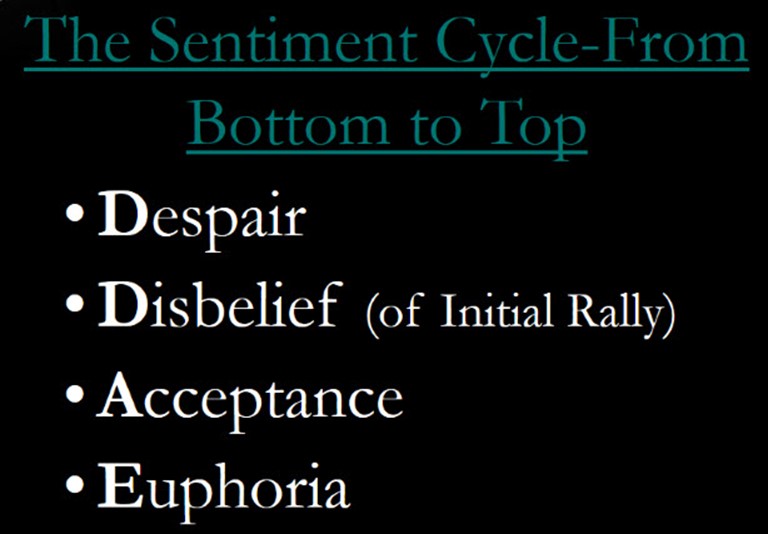

There are actually four distinct and identifiable stages of investor sentiment. We’ve already discussed the despair that is the characteristic of market bottoms and the euphoria that occurs at market tops. Initial rallies off market bottoms, as well as the initial declines off market tops, are each greeted with disbelief, as investors are very reluctant to accept the possibility that these counter-trend moves are anything but temporary. Eventually, this new direction for the market becomes sufficiently established and sentiment enters the acceptance stage. So the sentiment sequence off a major bottom is despair, disbelief, acceptance, and euphoria; off a major top it is euphoria, disbelief, acceptance, and despair. In this context, it is easy to understand the old adages that «markets advance on a wall of worry» and «markets decline on a slope of hope.»

So if major market turning points are concurrent with extremes in investor sentiment, how do we identify these sentiment extremes? Constructing sentiment indicators can be a challenging process. As early as the 1950s, Humphrey Neill — author of the classic work on sentiment analysis called The Art of Contrary Thinking — said the following: «No problem connected with The Theory of Contrary Opinion is more difficult to solve than (a) how to know what prevailing general opinions are; and (b) how to measure their prevalence and intensity.» At Schaeffer’s Investment Research, we’ve spent decades adjusting and improving our quantified sentiment indicators of activity in the options market.

But there is a shortcut you can take to identifying the sentiment extremes that accompany major market tops and bottoms in the form of the information contained on magazine covers at these junctures. Since the purpose of a news or business magazine cover is to attract your attention, the themes on magazine covers tend to be widely known and almost universally accepted as significant. And such themes have generally been in place for a long enough period to have established themselves in the consciousness of the reader.

But when you think about an investment theme that is widely known, universally accepted, and in place for a long time, you realize these are the exact characteristics of those themes that attract the euphoria at market tops («The technology boom will last forever») or the despair at market bottoms («The financial debt crisis will lead to economic collapse»). In other words, there is a strong relationship between the frequency and intensity of investment-themed magazine covers and the existence of the sentiment extremes of euphoria or despair. And this means there is a strong relationship between the timing of these magazine covers and the timing of market tops and bottoms. And herein lies the value of these covers to you as an investor.

I’ll leave you with an example of a recent magazine cover I believe has strong potential to be as defining contrarian theme for many years to come. BusinessWeek magazine’s cover from August 13, 1979, entitled «The Death of Equities—How inflation is destroying the stock market» became a classic example of how extremes in investor despair can mark major stock market bottoms. Just two years later, the stock market entered the greatest bull market of modern time, a rally that encompassed almost three decades and in which the major market indexes climbed fifteen-fold. The despair underlying the TIME magazine cover of October 19, 2009, titled «Why it’s Time to Retire the 401(K)» marked the end of a very frustrating decade for investors and set the stage for the beginning of a new bull market. Of course, the news backdrop and the economic backdrop seemed to tell us something very different, as did the pronouncements of the many «experts» and gurus who came to the forefront during our difficult economic times. But this backdrop was very similar to the gloom that prevailed back in 1979, and one of the very few roadmaps available then to the astute investor indicating a very different and prosperous future was provided courtesy of the editors at BusinessWeek and their accurate reflection of investor despair.

As Humphrey Neill, that great contrarian from many decades ago, told us: «The crowd is most enthusiastic when it should be cautious and prudent and most fearful when it should be bold.»

Article by

Bernie Schaeffer