By Mark Hulbert

Published: Sept 17, 2015 3:09 p.m. ET

It might be hard to believe, but it’s true, as research since 1989 shows

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (MarketWatch) — Should bond investors be disappointed that the Federal Reserve decided on Thursday, once again, to postpone raising interest rates?

That very question seems ludicrous on its face. Everyone «knows» that bond prices fall as interest rates rise.

But, as Humphrey Neill, the father of contrary analysis, was fond of saying: «When everyone thinks alike, everyone is likely to be wrong.» And now appears to be just such a time.

Consider an analysis conducted by Ned Davis Research, the Venice, Florida-based quantitative-research firm. Upon analyzing the performance of the Barclay’s Long-Term Treasury Bond Index, the firm found that the long bond since 1989 has tended to perform better when the Fed’s policy bias has been toward higher, not lower, rates.

Far better, in fact, as you can see from the accompanying table, courtesy of Ned Davis Research.

| Fed’s interest rate policy bias | Annualized gain of Barclays Long-Term Treasury Bond Index | Percent of the time since 1989 |

| Tightening | 5.1% | 21.4% |

| Neutral | -1.1% | 35.4% |

| Easing | -0.6% | 43.2% |

Davis acknowledges that this result is «counterintuitive.» Nevertheless, as he explained in a note to clients earlier this week, it makes a certain amount of sense: «Once the news is out that the Fed is raising the fed funds rate, forward-looking investors tend to expect both inflation and growth to slow, helping bonds.»

The key is to wait until the Fed actually begins to tighten, of course, since until then its commitment to fighting inflation is more questionable. Currently, for example, Davis’ firm classifies the Fed’s rate bias as «neutral» — which, as you can see from the table above, is associated with the long bond producing an average total return of minus 1.1%, annualized.

Only once the Fed shifts its bias toward tightening do conditions for bonds become more favorable.

Another reason to wait until the Fed actually begins raising rates is that’s when bond market participants will most likely be most pessimistic. From a contrarian point of view, of course, their extreme pessimism would be a good sign.

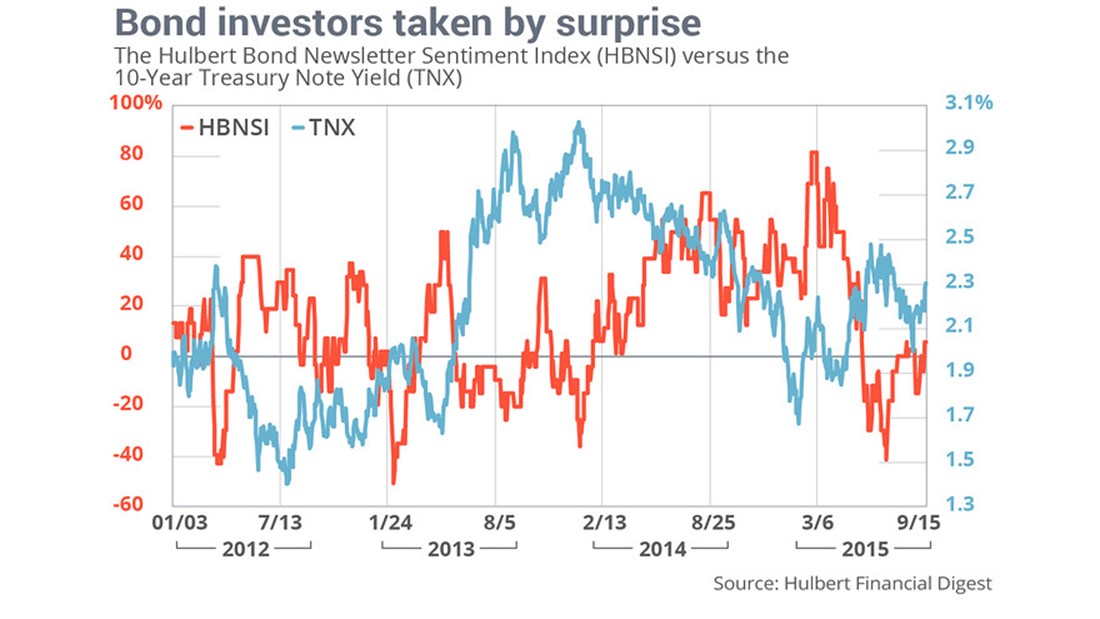

This is well-illustrated in the chart at the top of this column. It plots two data series over the past few years: the average recommended bond market exposure level among monitored bond-market timers (as represented by the Hulbert Bond Newsletter Sentiment Index, or HBNSI), and the CBOE’s 10-Year T-Note Yield Index TNX, -3.70% Notice that the lowest HBNSI levels tend to be followed by sustained periods of falling interest rates, just as contrarian analysis would suggest.

Currently, as you can see from the chart, the HBNSI is in the middle of its historical range, which means contrarian analysis is neutral on bonds’ near-term outlook. That’s consistent with the conclusion Ned Davis Research reaches based on the Fed’s current policy bias.

Don’t expect conditions to significantly change until the Fed finally makes good on its commitment to raise interest rates.