Don’t feel too bad, active managers. It’s not your fault

by Julie Verhage

June 15, 2015 — 7:41 AM VET

It’s no secret that active managers have struggled to outperform in the past five years while the S&P 500 and other benchmark indexes have seen big gains.

According to a Bloomberg report earlier this year citing Morningstar data, just 20 percent of mutual funds that pick U.S. stocks beat their main benchmarks in 2014, while 21 percent topped the indexes in the five years ended Dec. 31. (If you widen the time frame to 10 and 15 years, the winners rise to 34 percent and 58 percent, respectively). Unsurprisingly, investors have thus moved money to low-cost funds that mimic indexes.

So why is beating the benchmark seemingly so hard for the people paid to do so?

Morgan Stanley released a note this morning from a team led by Adam Parker with a few possible explanations.

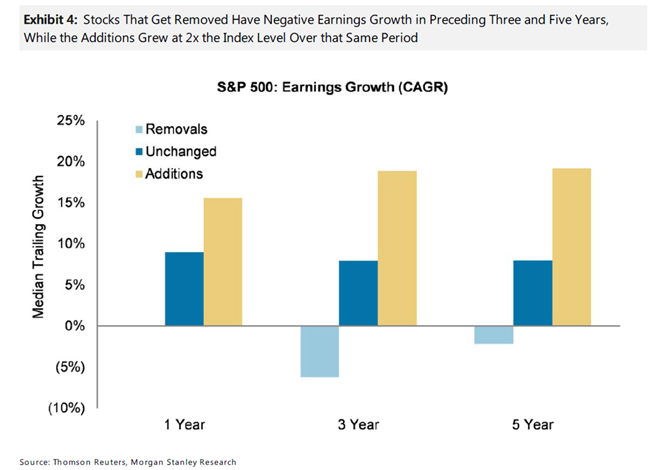

One of the main reasons is that when the S&P 500 removes a company and adds another, the new stock tends to be an outperformer:

The median stock removed from the S&P 500 has negative earnings growth in the preceding three and five year periods. The earnings growth of the companies added to the index was not only much superior to the companies removed but also much higher than those companies already in the index.

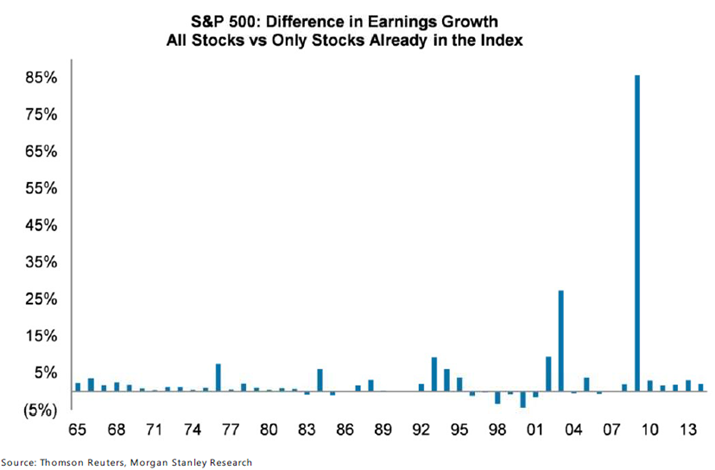

The note goes on to say that this causes an important bias in the overall index.

This causes a substantial, structural upward bias to the earnings growth of the S&P500 index. We decided to compare the earnings growth of companies in the S&P500 that were in the index the previous year, each year – the so-called «apples to apples» growth rate – to just the index level growth rate. The chart below shows the difference in the year-on-year earnings growth rate of the S&P 500 using all the stocks in the index vs the growth rate of the index excluding the new entrants. The median annual gap is 1.2%, and the index has beaten the «apples to apples» companies for 8 straight years.

This leads to the question of why the stocks added were outperformers. Parker and his team have this reasoning:

Why is there an almost permanent gap in earnings growth between the overall index and apples to apples companies? Because the new companies that are added to the index typically have much higher margins than both the companies removed and the surviving constituents …with faster prior revenue and earnings growth, and higher margins, the stocks added to the index typically have performed much better over the few years before their inclusion.

Thus Morgan Stanley’s advice to active managers is to avoid companies in the S&P 500 that have «poor [earnings per share] growth, very low margins and negative price momentum,» such as Apollo Education and Energizer Holdings.

Instead, you should look at companies outside the index with the exact opposite features. Morgan Stanley says these include Sonic, Madison Square Garden, and Illumina.